|

|

From The Witcher and Cyberpunk to Vampires and Outer Space: Jakub Szama³ek on Darkness, Choice, and Writing Without Limits8/1/2025

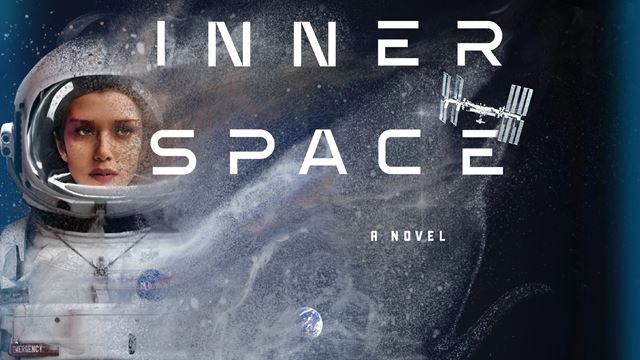

In our interview, he talks about the power of player agency, the brutally short 30-day time limit that cranks up the tension, and how his daughter’s fascination with space led him to write the novel Inner Space.

|

From the smoky taverns of The Witcher 3 to the neon-lit sprawl of Cyberpunk 2077, and now the dark dominions of the upcoming Blood of Dawnwalker, writer Jakub Szamalek has built stories that challenge players to reflect on their own decisions. After years at CD Projekt RED, he co-founded Rebel Wolves to experiment with a “narrative sandbox” and offer players unprecedented freedom — including the option to abandon heroism and let people face their fate. In our interview, he talks about the power of player agency, the brutally short 30-day time limit that cranks up the tension, and how his daughter’s fascination with space led him to write the novel Inner Space.

You’ve worked as a writer on iconic titles like The Witcher 3 and Cyberpunk 2077. Looking back, what aspects of those projects most profoundly shaped your approach to storytelling?

The Witcher 3 was the first video game I ever worked on. I had to learn quite a few things - and on the fly, too. The most profound takeaway from that project was realizing just how unique games are as a medium for storytelling. I found out how important it was to provide players with a sense of agency, and to maintain a strong connection between them and the protagonist. The moment that link is broken - say, because your character says something you disagree with, or because you’re supposed to do something you don’t want to do - immersion is gone.

Cyberpunk 2077, on the other hand, taught me tons about the importance of layering your story. That is, tell the most important bits in dialog scenes, and use all the other storytelling elements - say, background chats, in-game television and internet, onscreens - to provide additional context which enriches the tale you’re weaving. That way, your exposition is less heavy-handed, and players feel rewarded for exploring the world and paying attention to detail. So the deeper you dig, the more you find and the more hooked in the story you become.

What motivated you to leave CD Projekt RED and co-found Rebel Wolves? Was it a desire for more creative control, a different team culture, or something else entirely?

I’m deeply grateful for everything I learned at CD Projekt RED and I wish all the best to my friends who still work there. I guess I just felt it’s time for a change, to look for a greener pasture. Setting up a new studio seemed like the logical next step, and I’m very glad I took it. Rebel Wolves is an exceptional environment to work in.

The Blood of Dawnwalker introduces a dark fantasy world with vampiric themes and moral ambiguity. What inspired you to explore that kind of setting, and what do you hope players will take away from it?

hat’s a good question - for whatever reason I’ve always been drawn to dark fantasy settings, and the same can be said for most of the co-founders of Rebel Wolves. Maybe it’s because we all grew up in Poland, and our history is steeped in blood. I guess we just can’t help but see the world in grimmer colors than most? Which also means we’re naturally inclined to ask questions about the nature of evil – its sources, ways of standing up to it. I think these themes are extremely relevant to us all today, and I hope players will enjoy engaging with them. I hope Dawnwalker will be both a thrilling ride and something that makes you think, fine-tune your moral compass.

The story in Dawnwalker unfolds over just 30 days. Why did you choose this tight narrative structure, and how does it affect the pacing and emotional stakes?

It comes from the observation that most open world games have issues with presenting stakes believably. You’re told to take care of some urgent issue - but the game then patiently waits as you’re running around picking up herbs for crafting or playing minigames. And so you stop treating NPCs and whatever issues they have seriously - you know it’s only make-believe.

We wanted to tackle this issue, find a way to up the ante - and so, increase players’ immersion and ultimately, satisfaction. Introducing time as a resource seemed like an interesting direction to explore.

I’d like to use this opportunity to emphasise, though, that Dawnwalker won't have a real-time clock - time will only progress as you’re completing quests or engaging in particular game mechanics. So you don’t have to rush as you explore, or panic when someone calls you as you play - you can step away from the game and nothing will happen. But when someone asks you for help, you need to ask yourself - do I care enough to spend time to deal with this? And this adds another layer of non-linearity, because choosing to ignore someone will have consequences, too.

Would you describe Dawnwalker more as a personal, intimate character journey or a grand narrative epic? And how do you strike the balance between those two?

Balance - that’s the key word. We’d like to marry the two, so you feel like you’re on an awesome fantasy adventure, and yet the people around you seem real, fully fleshed and relatable. Some quests will offer stunning vistas and lots of exciting action, whereas other beats might have you engage with characters in more intimate settings. And as a player, you’ll have control over which kind of a story you’d like to engage with next. I think this points to one of the powers of video games - that you hold the reins, direct your adventure, in a way you couldn’t in traditional media.

Your games are known for complex, morally gray characters. How do you continue to evolve that kind of nuanced storytelling in Dawnwalker?

The key design principle behind Dawnwalker is the narrative sandbox. What we mean by this term is an open world game where there’s no distinction between side quests and main quests - there’s just the starting point and a goal you are supposed to reach. How you do it it’s entirely up to you. There are multiple storylines you can decide to engage with, but you may as well skip them all and still complete the game.

This approach allows for even more flexibility and non-linearies, which, in turn, translates into more freedom for players to shape the relationships with key NPCs as they see fit. For example, there’s very, very few people you cannot kill in the game. We put maximum emphasis on player agency - and hope that this will allow for truly unique and personalized playthroughs.

Let’s talk about your upcoming novel Inner Space, set aboard a space station during a time of global conflict. Where did the initial idea come from, and what drew you to this particular setting?

It all started with my daughter, Matylda. When she was little, she was fascinated by space, the cosmos, and so on, and she had LOTS of questions about it. I quickly realized I’m not qualified to answer them to her satisfaction, so I started reading about space and the more I read, the more I wanted to know.

Then, one summer, we took Matylda to the Space Museum in Toulouse. There’s a life-size replica of the MIR space station there, and you can actually step inside it. And the very moment I did, I felt claustrophobic. The space was tight, there were wires and buttons everywhere, everything looked industrial and drab. And then it struck me - this is where people spend months, flying through cold, lethal void? Why would anyone do it? And what if you’d be stuck there with someone you hate?

What were the biggest creative differences for you between writing a game script and writing a novel? Did you find it liberating—or limiting—not having to account for player choice?

Good question! I guess both? I love the element of choice in video games - what a wonderful way to introduce some tension, to grip someone’s attention. But of course, it leads to nonlinearities, and nonlinearities very quickly lead to massive headaches. While working on a video game story - especially one set in an open world - trying to stay on top of the network of choices and consequences is a task in itself.

But then, writing a novel I don’t have to worry at all about budgets or technical feasibility - anything I put on paper works, and there’s no need to consult anyone on anything… At least, until the book ends up on the editor’s desk.

Did writing Inner Space reveal anything new about your voice or storytelling instincts that surprised you?

I was surprised by how much fun I had dealing with constraints. The ISS offers limited space, and there’s precious little room for action - to keep things believable, I had to keep my characters civil for most of the intrigue. So all the tension had to be subtly, through descriptions of the station itself - this unbelievably sophisticated yet fragile work of wonder - and dialog. Initially, I was a bit daunted by the scale of this challenge, but the more I wrote, the more I enjoyed it. Felt like I was writing on “level hard” and still getting ahead, and that’s pretty satisfying!

Do you see Inner Space as a standalone work, or do you already envision returning to that universe in some form—perhaps even in a game?

It’s definitely a stand-alone title, but one that could be easily adapted to other media. I can totally see it as a movie, similar in tone to “Gravity” or “First Man”, or as a video game, where you get to explore the cramped, twisting ISS looking for clues.

Going forward, do you imagine yourself focusing more on novels, returning to large-scale game narratives, or continuing to explore both worlds in parallel?

I’d love to do both at the same time, but that’d be too much pressure - as much as I enjoy writing, I need to step away from the keyboard every once in a while. For now, my full focus is on the Blood of Dawnwalker - it feels we’ve got something very special on our hands with this game and I want to make sure it gets all the attention it deserves.